Be a Part of the Fight to End Alzheimer’s

Be a Part of the Fight to End Alzheimer’s

The millions of people impacted by Alzheimer's disease need your help. Your generosity can help us provide care and support to those facing the challenges of Alzheimer's and advance global research. Please make a gift today.

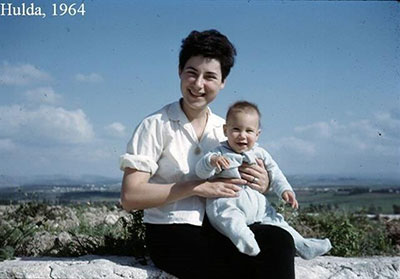

Donate NowBy the time she gave me all her cookbooks, Mom had almost entirely stopped cooking. She still made sandwiches for lunch, and endless cups of tea, but her more extensive culinary skills had dwindled to zero. We didn’t know exactly what “stage” of Alzheimer’s she had entered, but we recognized it as another in a series of declines.

With Daddy cooking on a daily basis, we joked that he had found his true passion. After years of being a chemist, he’d brought his scientific expertise into the kitchen. And Mom deserved to sit back and let him do the work after all her years of service.

With Daddy cooking on a daily basis, we joked that he had found his true passion. After years of being a chemist, he’d brought his scientific expertise into the kitchen. And Mom deserved to sit back and let him do the work after all her years of service.As a reaction to Mom’s diagnosis, I made a commitment to visit my parents on a weekly basis. The idea was to provide as much support as I could as their lives slowly changed. Not only did I want to comfort Mom through this emotional turmoil, but I wanted to counter Daddy’s initial desire to ignore or pull Mom back — often painfully and in anger — from her altering reality. I arranged my schedule so that I could visit my parents in their home in Netanya — a coastal city in Israel — every Tuesday. My challenge was to keep Mom occupied so that Daddy could have a break.

It was a long haul. I’d take the 7 a.m. train from Beer Sheva to Tel Aviv, grab a shared taxi at the train station and arrive in Netanya by 9:30 a.m. My parents would meet me at the central bus station, and then Mom and I would make our way to my Grandmother Millie’s nursing home. When she turned 97, Booba, as we called her, didn’t remember that it was her birthday. Mom, bless her, knowing our birthdays were back-to-back, asked in all seriousness if I was turning 18. (No need to remind her—or myself—that I was almost 50!) As I watched Millie’s 24/7 Philippine caregiver washing, dressing and diapering my grandmother, I kept thinking that soon we’d need to provide this service for Mom, too.

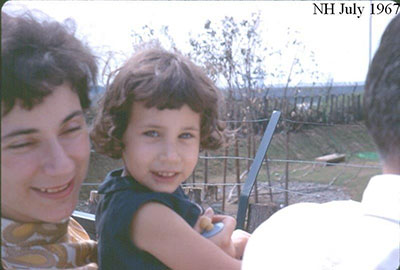

In some ways, she was already lost to me. The mother who had comforted me, taken an interest in my activities, and shaped my knowledge of motherhood, now seemed younger and less capable than I was.

In some ways, she was already lost to me. The mother who had comforted me, taken an interest in my activities, and shaped my knowledge of motherhood, now seemed younger and less capable than I was.Even something innocuous like saying the “Grace after Meals,” a blessing that religious Jews recite after they eat a meal with bread, became problematic. As I sat at Mom’s table, I recited: “God of compassion, bless my father and my mother, my teachers, hosts of this household.” At first, I felt sad saying those words. Was Mom still my teacher? How could she be? She had taught me many things when I was growing up, some quite practical (how to check eggs in a carton before you buy them), others intangible (that children thrive when you love them unconditionally). But now?

Still, I looked forward to Tuesdays. I saved my errands so that Mom and I would have some direction to our wanderings. We had fun together! We roamed the bustling streets of Netanya window shopping and telling jokes, laughing at all manner of things around us. We stopped for coffee and sipped our drinks in view of the azure Mediterranean. I tried hard to keep our outings stress free. If it meant bending the truth to fit Mom’s reality, that’s what I did.

Still, I looked forward to Tuesdays. I saved my errands so that Mom and I would have some direction to our wanderings. We had fun together! We roamed the bustling streets of Netanya window shopping and telling jokes, laughing at all manner of things around us. We stopped for coffee and sipped our drinks in view of the azure Mediterranean. I tried hard to keep our outings stress free. If it meant bending the truth to fit Mom’s reality, that’s what I did.Sometimes, she informed me she was only 46, making me the older of us two. Or she’d say, puzzled, “Daddy went to work and hasn’t called all day.” I could never tell if she were referring to my dad, who’s been retired for years, or her dad, who, sadly, passed away 19 years ago. Often, she’d ask where “Jack” was, thinking he was a different person from “Daddy.” If I tried explaining that “Daddy” and her husband Jack were the same person, she would utterly reject it. It was easier to lie. “Oh, I spoke to him today. He’s fine. He’ll be home soon.”

“But what has he been doing?” she’d ask.

“You can ask him when you see him,” I’d suggest, thereby setting up an open-ended conversation we replayed many times.

Sometimes she’d admit to being frightened by her memory loss. Other times she wanted to be held. The first time she came into my arms, I felt awkward. She hugged me tight and cried against my chest. I gave her comfort, of course, but I realized my role of child was shifting. What I wanted—to remain her child—could not last.

As a memory exercise, I tried to get her to remember how to prepare some of my favorite dishes that she had made while we were growing up. Clarity would often elude her, though on some days, she’d give me exact measurements and describe the cooking process without hesitation.

There was one recipe I never did succeed in discovering. I remember a luscious trout dish with roasted almonds, grapes and a creamy cheese stuffing. It was absent from all of Mom’s cookbooks, and she never remembered the dish when I prodded her about it.

There was one recipe I never did succeed in discovering. I remember a luscious trout dish with roasted almonds, grapes and a creamy cheese stuffing. It was absent from all of Mom’s cookbooks, and she never remembered the dish when I prodded her about it.I do believe that Mom is still teaching me new things. I am learning to accept her reality, to explore ways of stimulating her and keeping her active. I am learning that time can shift as past memories become the present; and that laughter is a precious commodity. I am learning the art of patience. And I am learning to let go of the frustration I feel in losing myself when I am with her.

Reprinted with permission from "The Lost Kitchen: Reflections and Recipes of an Alzheimer's Caregiver", Black Opal Books, 2019. © 2019 by Miriam Green.

About the Author: Miriam Green is the author of "The Lost Kitchen: Reflections and Recipes from an Alzheimer’s Caregiver" (Black Opal Books, 2019). She writes a weekly blog at The Lost Kitchen, featuring anecdotes about her mother’s Alzheimer’s and related recipes. Miriam’s poetry has been published in several journals, including Red Wolf Journal, Poet Lore, The Prose Poem Project, Ilanot Review, The Barefoot Review and Poetica Magazine. She holds an M.A. in Creative Writing from Bar Ilan University and a B.A. from Oberlin College. You can find Miriam on Facebook and on Twitter.

Related:

Caregiving

Support Near You

Food and Alzheimer’s